I am an avid lover of ancient history. My weekends as a child were spent cloistered in my aunt’s library reading mythology. I enjoyed books like The Iliad, The Odyssey, and comic book short stories from the Bhagavad Gita. As cheesy as it sounds, my love of history turned into a passion when I saw the movie Stargate. I was hooked on history like never before; I read encyclopedias to learn more about Ancient Egypt and went so far as to attempt to learn hieroglyphics. A few years ago, while working at Indigo Books, I came across a coffee table book on King Tut, The Treasures of Tutankhamun.

It was like any other history book, or so I thought, until I opened it up. When I say coffee table book, I mean the ones we all think about: it’s there for decoration, a nice talking point but nothing that requires in-depth thought or conversation, but has lots of glossy pictures. I was surprised by the level of detail that went into the publication of this book. It had all the trademarks of a coffee table book: big, glossy pictures, minimal text, and lent itself to a conversation piece, but could be relatively ignored. However, this book was different.

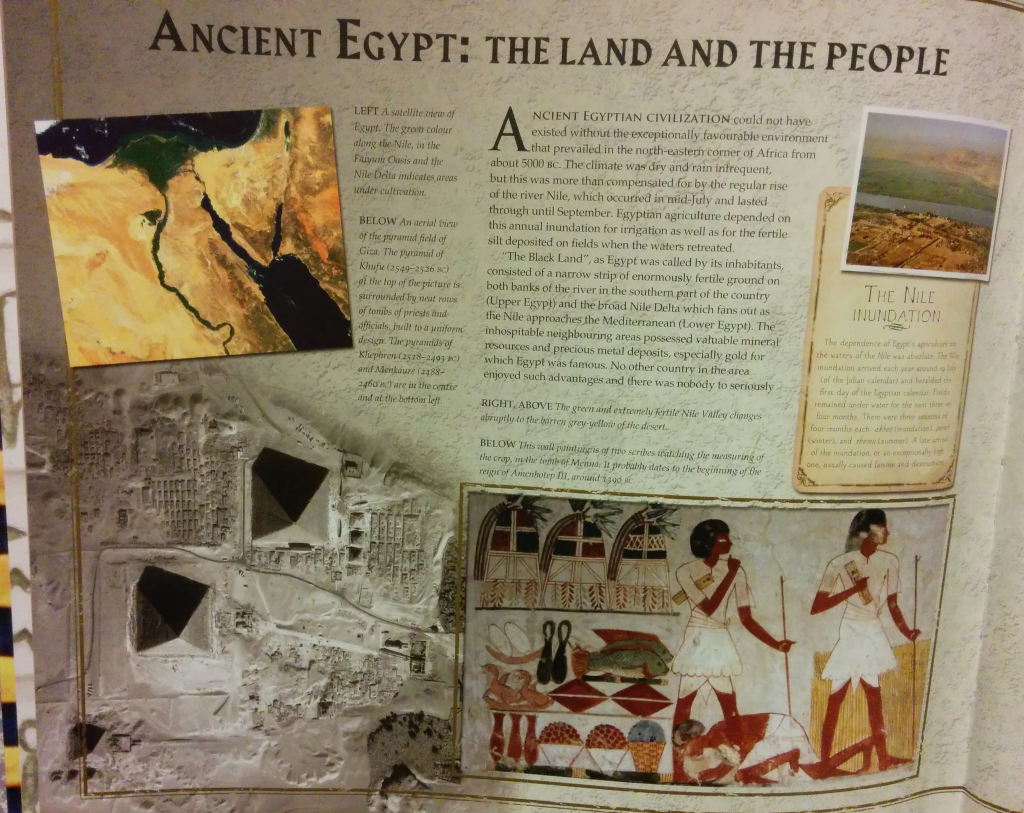

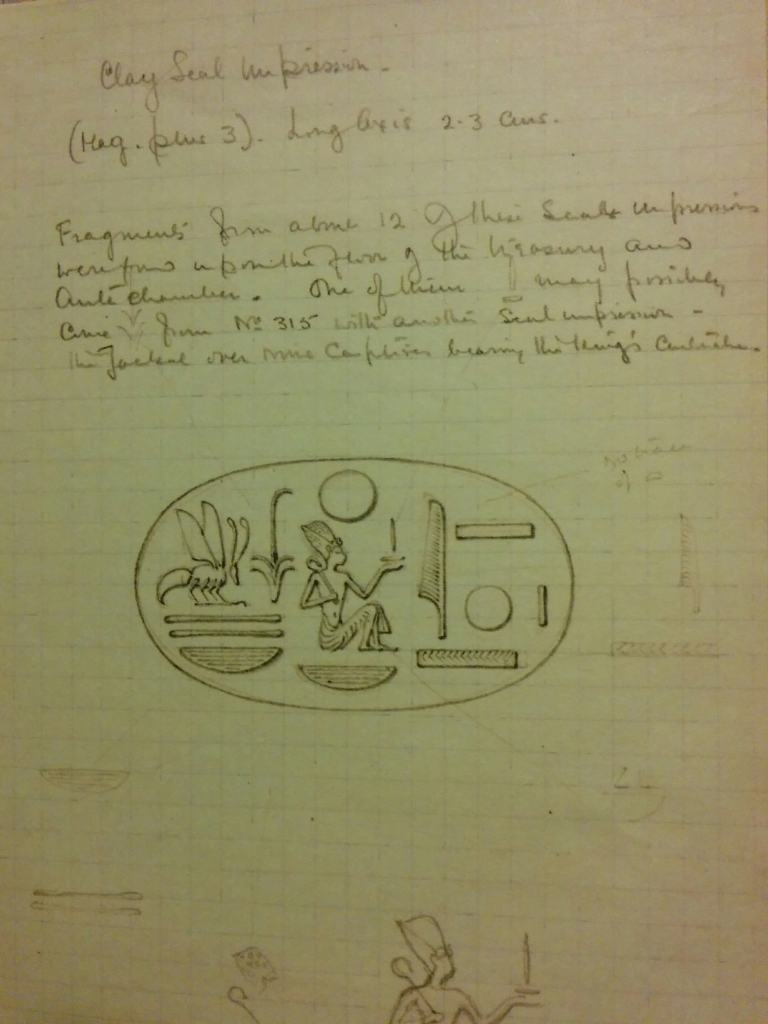

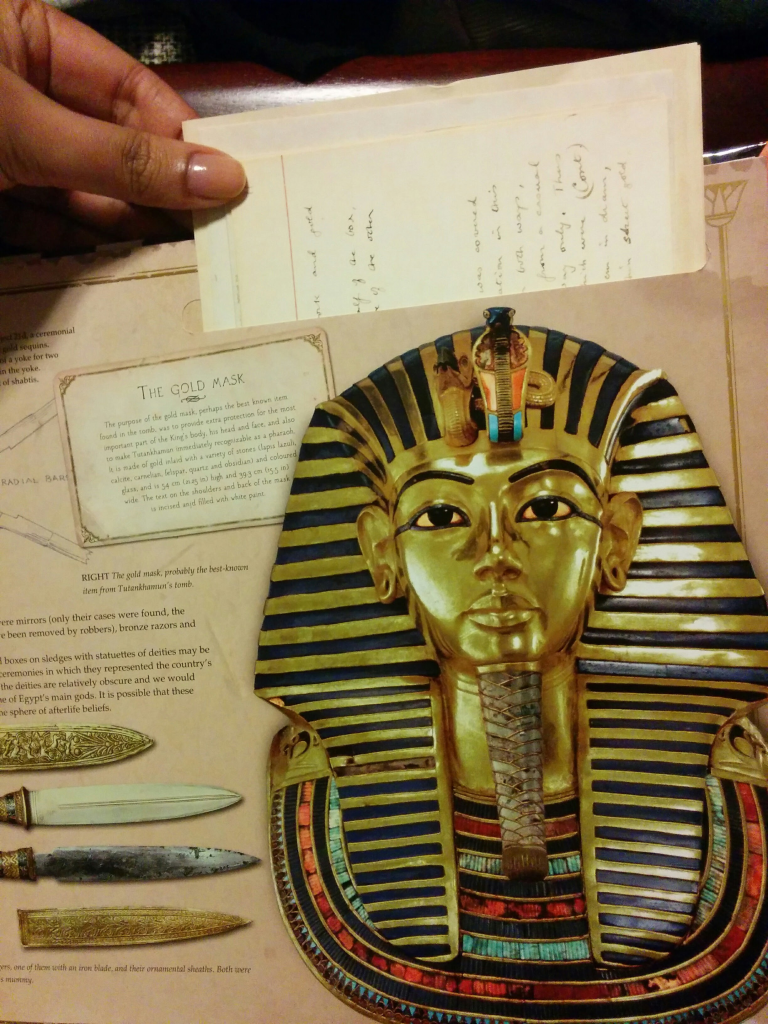

Among the glossy pictures and historical narrative were little leaflets, maps, photographs, letters, and brochures inserted into cut-outs or papyrus-looking envelopes that surrounded the monumental discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The purpose of these additions was to create an immersive experience for the reader by drawing them back in time to 1922 with the correspondence of Howard Carter, using replicas of original photographs, handwritten letters and maps. I was intrigued by the attention to detail of these facsimile artifacts. Care was taken to reproduce the look and tangible feel of paper as they were originally written and drawn on, instead of flashy updated pieces. Even notes and drawings done in pencil look genuine. It is this feeling of authenticity that makes the reader feel as if they were part of the narrative. Instead of a passive reading experience, the additions in this book make it interactive and exciting to engage with. It is this interactivity that makes this book different from most coffee table books and historical non-fiction that I have come across.

However, after reading Robert Darnton’s, “What is the History of Books?” I started to look at this piece slightly different. Darnton talks about the historical perspective he gained from the letters he read from the different people involved in the publication of books. I asked myself, “What version of history is this book capturing? Do we gain additional insights into the lives of those involved in the uncovering of the tomb or just a reinforcement of the popular ideals by those who write history?” It would be interesting to see the entire collection of Carter’s correspondence and not the snippet that has been revealed in this book.

Finally, I would like to address issues of digitization for an item such as this book. Current digitization efforts or e-book readers would fail to deliver the dynamic experience of The Treasures of Tutankhamun. I could potentially see this being recreated through a website or some other interactive format. What type of interactivity does a digitized medium invite? Efforts to digitize materials do not concern themselves with how the meaning of a piece changes when interpreted through a different format. How would The Treasures of Tutankhamun be digitized with all its moving pieces? Preservation and access are important but are we conveying the same meaning and experience to the reader?

Citation

Jaromir Malek, The Treasures of Tutankhamun (London: Andre Deutsch, 2006).