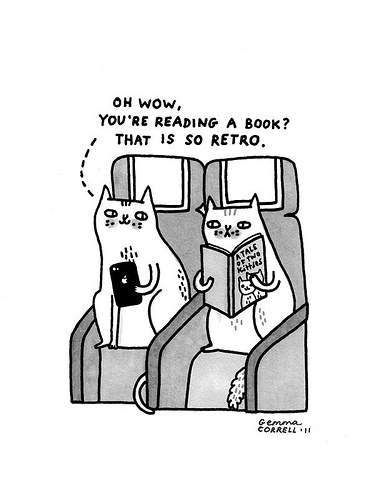

Alright, bear with me on the cheesy title for this post. In all seriousness, I think this cliché accurately sums up how books and bookish things have progressed throughout the ages. To this end, what I would suggest to someone in the past about the future of books and reading is that ‘the book’ will not only persist, but it will do so with remarkable similarities to books that past citizens of time have known, understood, and loved. When considering how ‘books’ have evolved, from cuneiform tablets, to papyrus scrolls, wax tablets, bound codices, pulp paperbacks, and right up to audio books, the Internet, and digital e-books, what is remarkable is not the degree of change, but the degree of similarity. What we’re dealing with here are differences in degree, not in kind.

In a world where immense changes and developments have been made in areas such as science, technology, medicine, transportation, and the like, it is pretty incredible to think that books, for the most part, look quite similar to their nearly five-hundred year old counterparts. Take for example, the fact that the codex form has persisted, despite death knells for the ‘end of the book’ tracing back over a hundred years. Octave Uzanne, in his 1894 “The End of Books,” foretold, “If by books you are to be understood as referring to our innumerable collections of paper, printed, sewed, and bound in a cover announcing the title of the work, I own to you frankly that I do not believe (and the progress of electricity and modern mechanism forbids me to believe) that Gutenberg’s invention can do otherwise than sooner or later fall into desuetude as a means of current interpretation of our mental products” (223-224). Even his prophecy of “phonographic literature,” realized in the audio book, did not prove to do away with the printed codex entirely. New technologies such as e-books, widely presumed to be the book’s successor, are inextricably caught up in the look and feel of printed books, as Johanna Drucker puts it, “electronic presentations often mimic the kitschiest elements of book iconography, while potentially useful features of electronic functionality are excluded” (2009, 166).

What can account for this lack of dissimilarity? I wonder if it comes down to something Drucker mentions about the difference between “the way a book looks” and “the ways a book works;” she writes, “think of the contrast between the literal book – that familiar icon of bound pages in finite, fixed sequence – and the phenomenal book – the complex production of meaning and effect that arises from dynamic interaction with the literal work” (2009, 169). Certainly changes in technology have meant differences in how we interact with words – whether on a page, a screen, through a hyperlink…all of these things have changed our reading experience. Yet, with only a difference in degree, perhaps the story of the book over the last few hundred years has been a narrative of continuity, and not change? Despite Andrew Piper’s assertion that digital reading may not in fact be ‘reading’ at all, but something entirely new (2012, 46) – it seems that many of our traditional ways of being with books and bookish things still apply.

As for the future of the book, Robert Coupland Harding wrote in 1894: “Will moveable types still remain? We think they will. Steam and devil-driven though the world may be now – dazzled by electric light and thrilled by galvanic motors as it will be in years to come – there must still remain classes of work that no mechanism can perform” (85). In some ways, Harding’s statement still stands true. In this hybrid reading environment, with print and digital co-existing, it would seem that the ‘work’ of reading can still occupy a decidedly traditional space, while it changes, morphs, and adapts. Umberto Eco, in This is Not the End of the Book, writes of the future, “One of two things will happen: either the book will continue to be the medium for reading, or its replacement will resemble what the book has always been, even before the invention of the printing press. Alterations of the book-as-object have modified neither its function nor its grammar for more than 500 years. The book is like the spoon, scissors, the hammer, the wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved. You cannot make a spoon that is better than a spoon” (2011, 4).

I would agree wholeheartedly, and yet, I don’t think that with regards to bookish pursuits we are entirely in the clear. The Economist’s essay on the future of the book, “From Papyrus to Pixels,” notes that, “In the past decade people have been falling over themselves to predict the death of books, of publishers, of authors and of bookshops, even of reading itself. Of all those believed at risk, only the bookshops have actually suffered serious damage” (2014). To this I would add, libraries. Not to get all doom and gloom here, but library cuts and closures are about as close to the ‘death of the book’ as we’re coming – Leah Price notes, “Writers foresaw space travel, time travel, virtual reality and, endlessly, the book’s demise; what they never seem to have imagined was that the libraries housing those dying volumes might themselves disappear” (2012). In 1955, Lester Asheim wrote that, “The library of today is still essentially a book agency, and our training, practice, and outlook are book-oriented. The library of the future may or may not be primarily a book agency. If it is not, those of us who limit our attention to the book may find our libraries, if not completely discarded, at least relegated to a position of considerably reduced importance and vitality. On the other hand, if the library of the future should continue to be a book agency, it will be an effective one, not through our blindly devoting ourselves to the service of books in and for themselves, but because as librarians we will have analyzed and understood the unique role of the book which qualifies it to serve new and developing needs” (282). For once, a projection we should take heed of. So, I guess if I were to go back in time and give a warning about the future it would be this – forget about the death of the book, it will be just fine, but direct your attention to the library instead. Maybe it has been a bit of hubris that lead to a denial that libraries could ever disappear – whatever the case, it seems that libraries might do well to consider a difference in kind (to their collections, their services, their outlook) in order to survive (and thrive) into the future.

References:

Asheim, Lester. (1955). New problems in plotting the future of the book. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 25 (4): 281-292. http://www.jstor.org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/stable/pdf/4304463.pdf.

Drucker, Johanna. (2009). Modelling functionality: From codex to e-book. In SpecLab: Digital aesthetics and projects in speculative computing. (pp. 165-175). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eco, Umberto and Jean-Claude Carrière. (2011). This is not the end of the book. London: Harvill Secker.

“From Papyrus to Pixels.” (2014). The Economist. http://www.economist.com/news/essays/21623373-which-something-old-and-powerful-encountered-vault.

Harding, Robert Coupland. (1894). A hundred years hence. Typo, 8: 85. http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/etexts/typo/Har08TypoFCo.jpg.

Piper, Andrew. (2012). Turning the page (roaming, zooming, streaming). In Book was there: Reading in electronic times (pp. 45-61). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Price, Leah. (2012). Dead again. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/12/books/review/the-death-of-the-book-through-the-ages.html?_r=0.

Uzanne, Octave. (1894). The end of books. Scribner’s Magazine, 16 (2): 221-232. http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=scri;cc=scri;rgn=full%20text;idno=scri0016-2;didno=scri0016-2;view=image;seq=0229;node=scri0016-2%3A9.