Source: http://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/category/19th-century-women-writers/

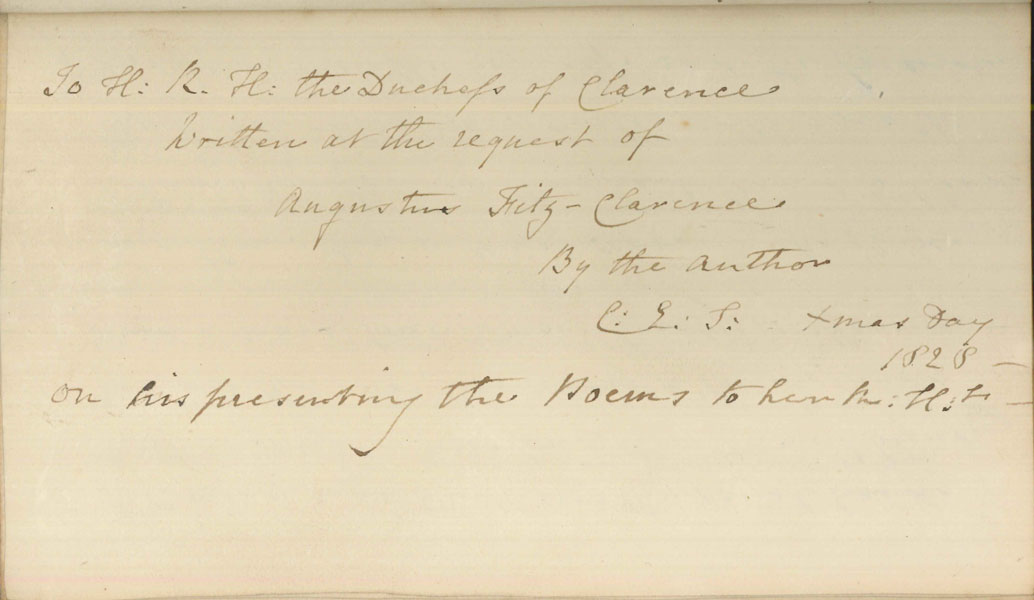

I think that if I could travel back in time, the message I would focus on relaying would be around medium as a reflection of current ideological state, and as something that is flexible and should be open to interpretation. I’m specifically thinking about the roughly 19th Century Anglo/ European audience as a useful target demographic to propagate this idea to, so as to avoid the discounting of manuscripts and letters as worthy candidates for the study of book history. This is in part inspired by one of my book history classes in which we looked at the letter writing of women in this time period and how there was often a dichotomy created between the authority of print and the less authoritative domain of handwriting or manuscript. This would be beneficial for expanding the scope of the field not just in terms of materiality, but also in terms of its socio-cultural engagement in history. The Future of the Book has shown us the flexibility of the definition of a text, and the multitudes of ways that stories can be told effectively outside of the traditional printed codex.

This particular insight might be addressed to a still developing field of book historians and scholars so that they might build up the field with a wider sense of what counts as important to the culture of books (and to consider to what degree it is valuable to draw lines of distinctions around what books are). Even as we turn our gaze towards the future, the boundaries between mediums become less clear. As Matthew Kirschenbaum notes “the tendency to elicit what is ‘new’ about new media by contrasting its radical mutability with the supposed material stolidity of older textual forms is a misplaced gesture, symptomatic of the general extent to which textual studies and digital studies have failed to communicate”(24). Perhaps, then, if we were not so rigid in our original definitions of the book, the field would not struggle to define itself and its breadth today.

Bibliography

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. “Editing the Interface: Textual Studies and First-Generation Electronic Objects.” Text: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual Studies 14 (2002): 15-51.

Figure 1. PDF

Figure 1. PDF

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Figure 1.

Figure 1. Figure 1.

Figure 1. Figure 2.

Figure 2.