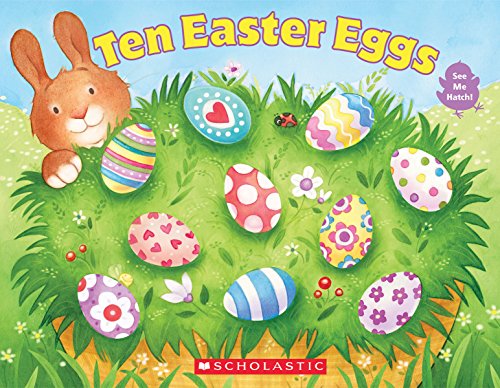

Bodach, V. & Logan, L. (2015). Ten Easter eggs. Scholastic: New York.

I left last Monday’s class thinking about the relationship between bibliographic form and meaning. What print books would be impossible to translate in a digital form without losing meaning integral to the text? An answer to this question was literally handed to me the next evening by a young girl during my shift at the Cobourg Public Library. She presented me with one of the library’s board books, Ten Easter Eggs, concerned it had been broken. For those unfamiliar with children’s library collections, a board book refers to a book designed for infants and toddlers with stiff, cardboard pages. In our readings this week Kirschenbaum and Werner write (2014) “… most digitizations focus on the value of the object as a text to be read” (p.419), board books are objects with value extending beyond their printed text. As a result, digitization of board books is difficult to achieve without losing meaning essential to the object.

Board books are designed not only to be read. Manufactured with durable materials, they allow for use specific to the developmental stage of infants: the reader may put the book in their mouth, or grab it by one page and wave it around. Ten Easter Eggs is an interesting board books as its pedagogical function extends beyond the lessons of the text (such as counting to ten, and simple addition and subtraction) to sensorial learning.

The book contains ten three-dimensional eggs. For example, page one contains one 3D egg and nine egg shaped cut-out holes, which reveal the other nine eggs contained in the book. As the page is flipped, a fuzzy chick made with felt is revealed below the egg. Page three now contains nine eggs and one felt chick. The verso pages contain egg-shaped holes. This process continues until ten felt chicks are revealed. This design allows the reader to explore the book with their hands, feeling the holes, the felt chicks and the smooth 3D eggs. This sensory experience could not be replicated in a digitized version of the text. Furthermore, eBook platforms such as eReaders or tablets are not designed for children to put them in their mouths or throw them around. As a result, the child’s relationship to the object would be shaped by greater caution in a digital format (enforced, most likely, by adults) and as a result, would look quite different.

I mentioned earlier this book was handed to me by a young library patron. She was concerned because several of the 3D eggs had been “punched-in” by previous readers, rendering their shape less than egg-like. Rather than understanding the book as damaged, this can be read as a productive interaction between the reader and the text-object. Through using the book in a way it was not designed to be used (applying great pressure to the eggs) the child reader has the ability to change the shape of the egg, creating a very different sensory experience for future readers. In this way the text effects meaning unintended by its designers.