This is also a post made long by pictures…

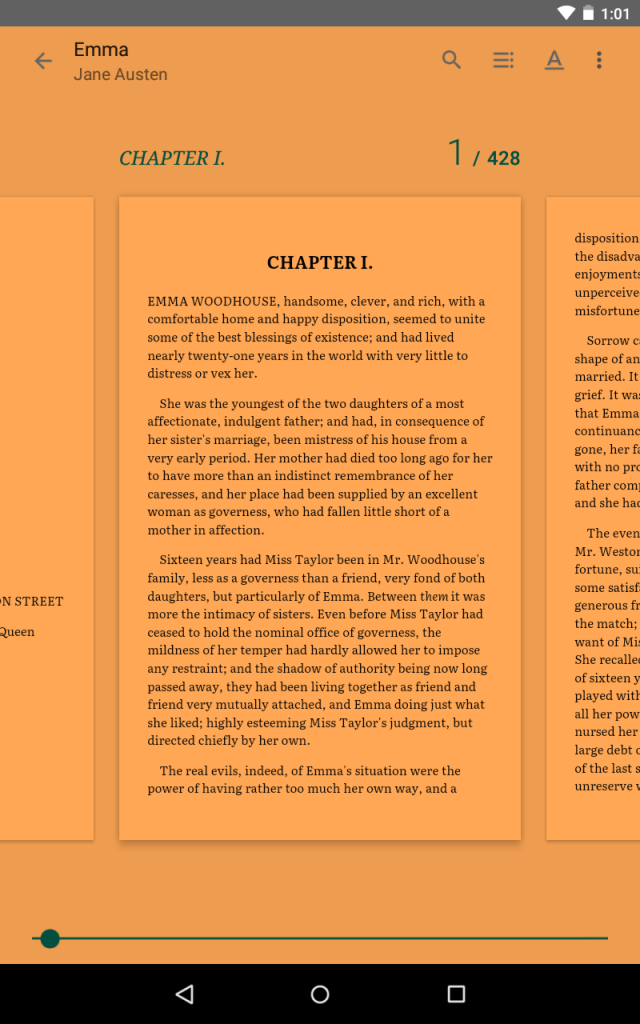

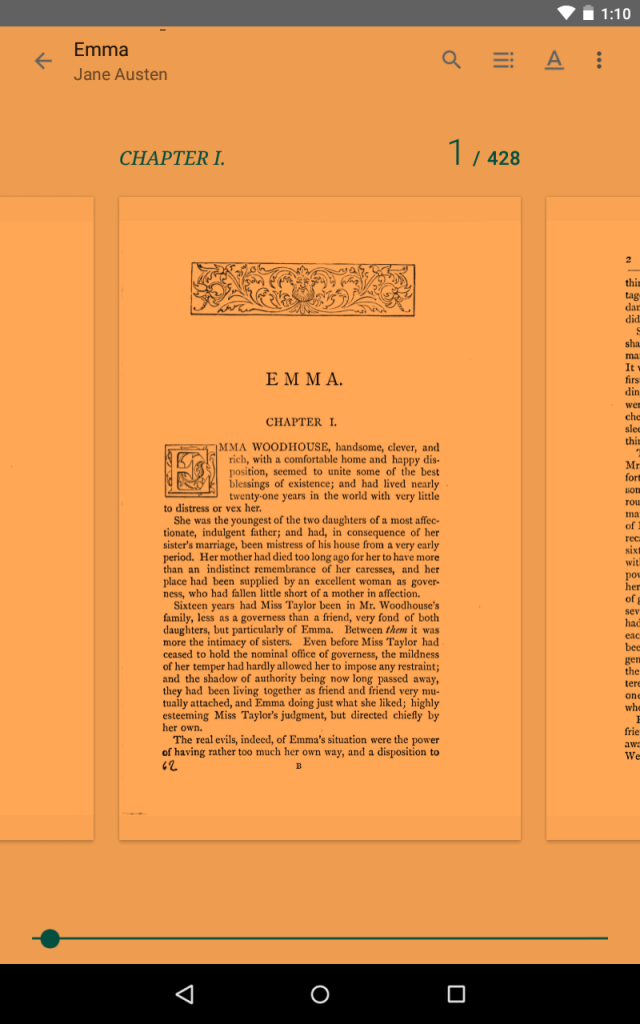

While not necessarily a remarkable example of a ‘digital page’, this week’s blog post did give me some greater insight into digital pages generally. I have a difficult time reading digital texts and have spent almost no time exploring the different interfaces and options that are available. That being said, when I was considering this topic, I remembered that I do own a nexus tablet (albeit one that mostly gathers dust). It was a gift, and at the time I received it, I can remember going onto Project Gutenberg and downloading some of their free EPUB style e-books into my Google books ‘library’. I promptly never looked at it since. I decided that this would be a good opportunity to explore it further. I chose Jane Austen’s Emma as my text of focus and found many fascinating features that I had no idea existed. To begin, there certainly is a seemingly greater freedom on the part of readers with regards to page layout, look, and design. The most macro view reminds me of Andrew Piper’s notion of ‘zooming’ – “if roaming expands the horizontal edges of the page, zooming bursts through the page’s two-dimensionality” (56). Using two fingers you can change the scale of the text in question to see an expanded view of the page that includes multiple fragments of the preceding and following pages (as well as extra-textual material and setting symbols) :

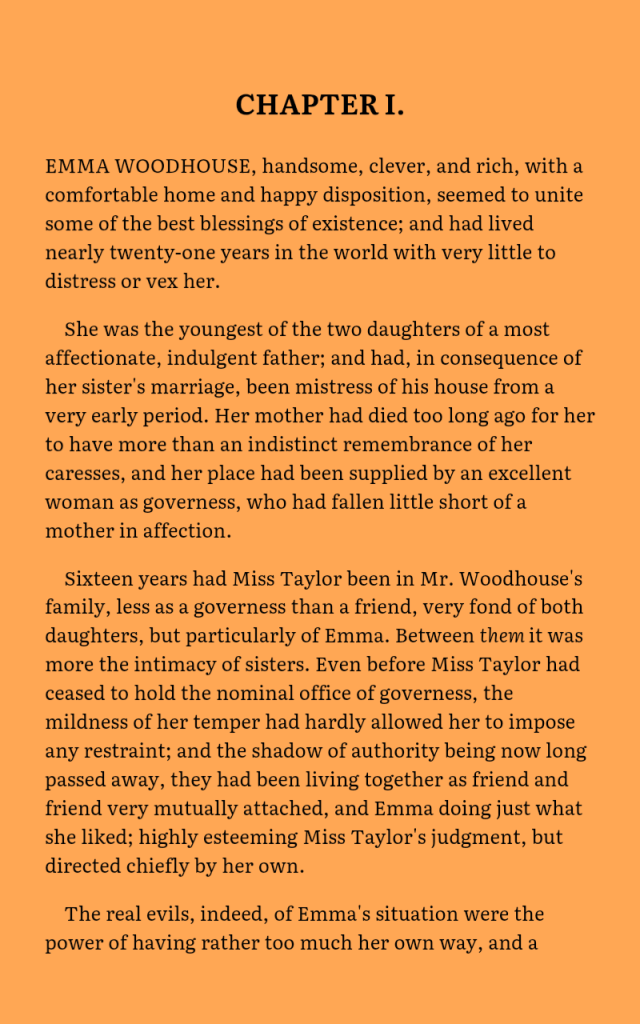

Alternatively, you can zoom in to the macro view of the page as a single unit:

On a side note – the funny amber hue of the page that you can see is the ‘night light’ feature, which claims, in romantic tones – “as the sun sets, Night Light gradually filters the blue light from your screen, replacing it with a warm, amber light that’s better for reading.” Who knew?

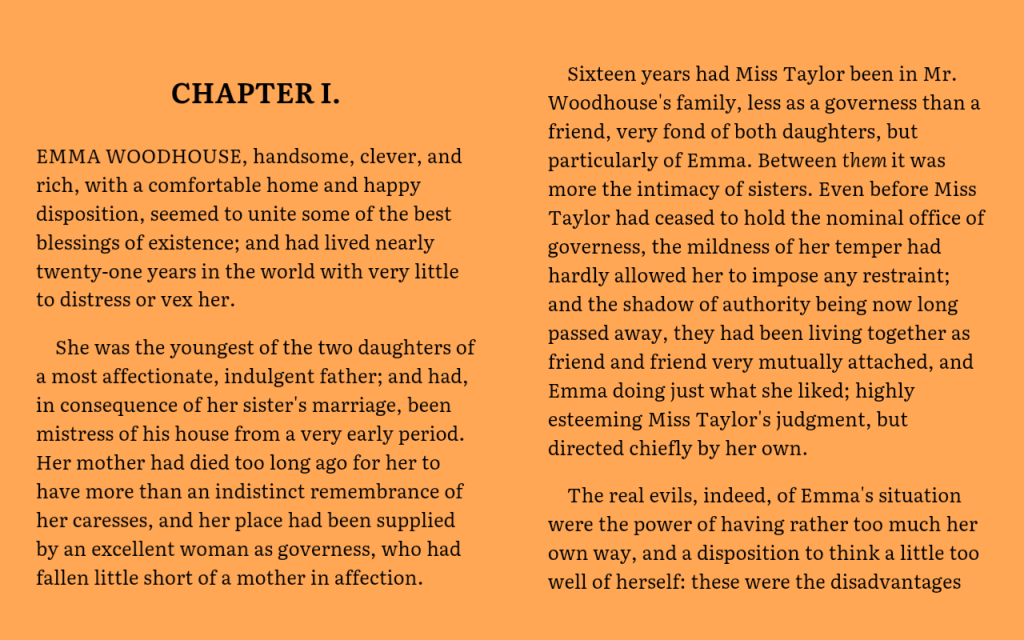

It turns out that if you rotate the tablet, the auto-rotate screen will provide you with both the verso pages and recto pages (although without a gutter margin…), thus bringing back Piper’s assertion of ‘pages as mirrors’ into the e-book equation; once again “pages face each other; they comment, reflect, illustrate, or confound one another” (52). Only in this mode can pages exist side by side.

Of course, in a digital text, the ‘pages’ are not a fixed unit of text (this is something I have always found unsettling – trying to read a text which moves independently of its page numbers). Thus, what you can see in this latest image is not in fact a new recto page, but merely an extension of the text on the verso side, which in the landscape view, can stretch out slightly.

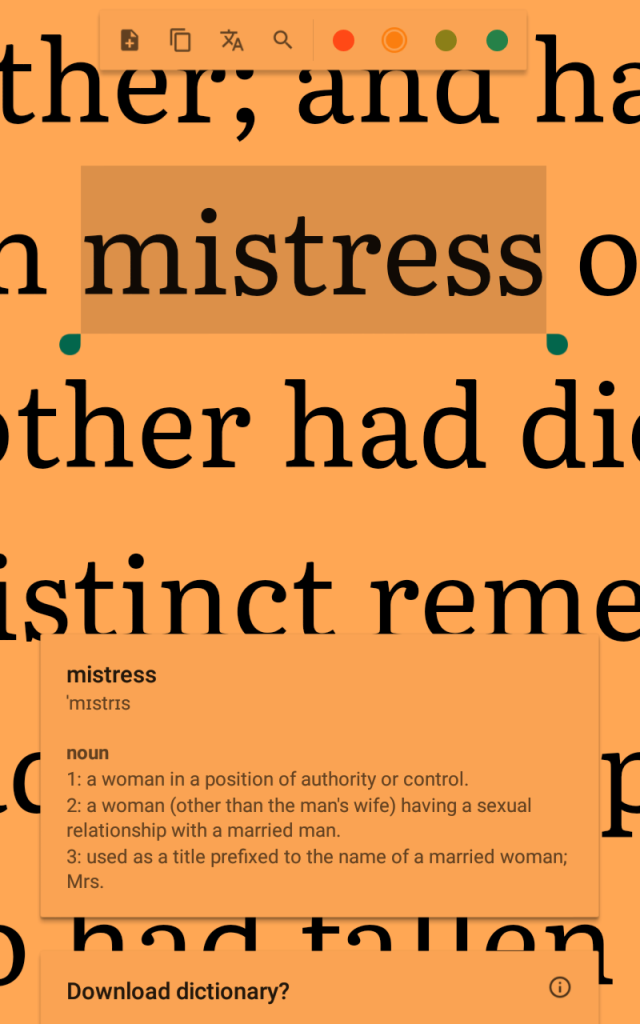

In playing around with the features, I discovered the ‘maxed out’ micro view, essentially where the screen is focused on a small handful of words – helpful for magnifying, although to the point where the words lose their context in relation to the page as a whole.

Here I also discovered some of the additional features (I’m sure seasoned readers of e-books are laughing at my naiveté by now…). Again, who knew that with just one finger tap you can copy, annotate, highlight, search, and define? The possibilities seem endless. What of Piper’s assertion that, “it may be that we should no longer even call this reading,” or that “we are breeding generations of distracted readers, people who simply cannot pay attention long enough to finish a book” (46) – what do these many opportunities and rabbit holes entail for the process of reading itself?

Another thing I have never been able to wrap my head around is the sort of generic, robotic seeming uni-font that most e-books employ. I discovered in my explorations that in this particular case I had the option to see the ‘original pages’ of the text (scanned by Google books):

I can’t help but wonder if the friendly and familiar ornamentation and illustrated initial helped me feel more at home with this variation of the page. On this note, I discovered the ‘read aloud’ setting, no doubt a wonderful accessibility feature – although in the advanced settings, found that you could opt for a ‘high-quality voice’ which claims to “use a more natural voice to read aloud” – so what of a more ‘high-quality page’? One that appears ‘more natural’? More than anything, I was struck by the strange physicality of the digital page (or lack thereof) – the digital ghost page requires such little human intervention – try interacting with, or try touching a physical book in the same way – it is utterly ineffective, clumsy, and potentially damaging (you would risk crumpled or ripped pages to say the least…). Once again, a different physicality of reading, the embodiment, the motions, has to be learned here – is not intuitive (at least at first). I found interacting with this book to be clumsy, like learning another language.

I am certainly intrigued by the options provided by digital texts within this type of platform, although I am hard pressed to imagine this digital hologram as a sort of stand in for the printed page; as Piper puts it, “the digital page, by contrast, is a fake, a simulation called up from distributed data. It is not really there” (54). This seems to be where I’m stuck – no matter how much I swipe, and zoom, and pinch, I just can’t seem to feel anything.

References:

Austen, Jane. (1886). Emma: A novel [Play Books EPUB version]. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/158.

Piper, Andrew. (2012). Turning the page (roaming, zooming, streaming). In Book was there: Reading in electronic times (pp. 45-61). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hey Marlena,

I am also quite inexperienced with eBooks and I really rather enjoyed reading you post. It felt like I was discovering new features with you. I have been a Jane Austen fan for many years and your post made me think of back to high school mandatory readings. Though I was a fan, I had many friends who struggled to get through Pride and Prejudice and understand it. For many reading a unique voice can make it hard to understand the story and the books may have vocabulary that students may not be used to. I know many students who would have found the resources such as definitions and spoken text incredibly helpful in understanding the story.

Kali

Hi Kali,

Thanks for your comment! I’m glad to hear that you enjoyed my exploration – it’s a relief to know I’m not the only one who is coming to these things anew. You make a great point about the possibilities opened up by digital reading platforms – I think the dictionary feature is a really fascinating built in aid. With regards to mandatory curriculum reading, I can imagine something like this would also help with parsing out Shakespeare, and other pieces that might be a challenge to engage students with. I wonder the extent to which this is being explored as an option and made available. I can remember one of the challenges being that all students in the class were required to have the same edition of the work in order to follow along and have the same page numbers. I think it would be great though if these issues were taken into consideration, as you point out, they could certainly improve students’ experience of the texts. That’s another great argument for not picking sides on the print vs. digital spectrum, as each has their unique features and people might take to them differently, and for different reasons!