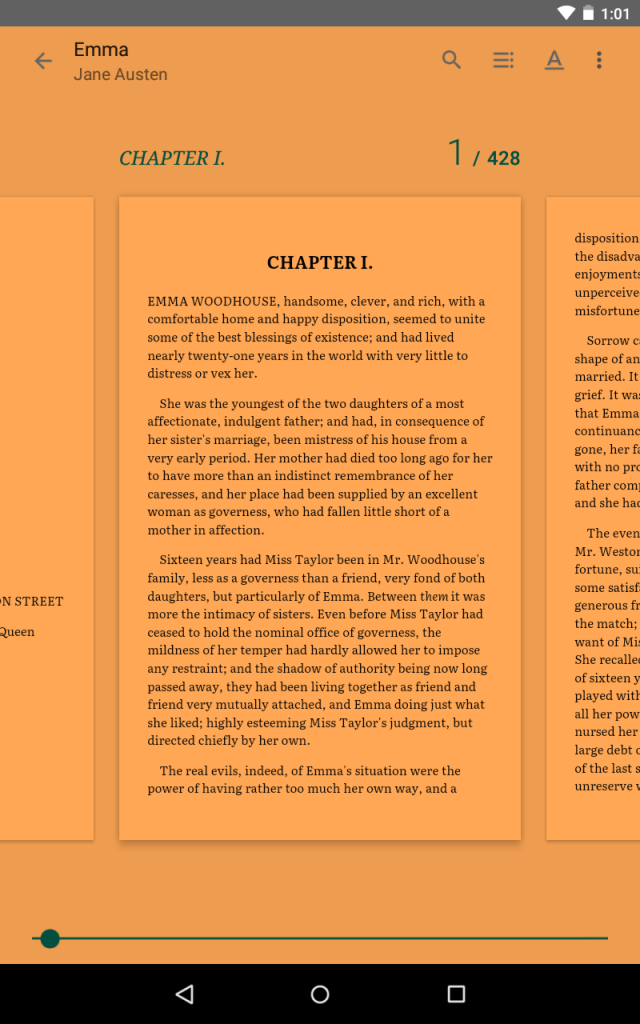

I have owned a Kobo ereader for about two years now and it’s impacted my reading habits in unexpected ways. I got an ereader particularly so that I could take out library books without waiting so long and read them without the migraines backlit screens give me after a while. I figured I would use it mostly to read library books, in particular nonfiction, which usually weigh about a thousand pounds per book. I was wrong.

Not long after I got my Kobo, it seemed like library ebooks exploded in popularity. Suddenly the holds lists I had been hoping to avoid were digital and even longer, as there are generally less digital than physical copies in the system. It became easier to get physical library books than ebooks, especially if they were in paperback. I still read the same amount of physical library books as I did before.

Certain types of writing influence me. I find it difficult to read authoritative writing (most nonfiction) on an ereader. For some reason, I can’t concentrate on it. Recently, I got an ebook on rabies out from the library. I get periodically obsessed with infectious diseases, and, having read a bunch of zombie books, was burningly curious about this devastating, zombie-plague-like infection. I opened it several times with great excitement, read a page, and found I couldn’t remember anything I had read. I’m curious to see if the physical copy will grab me. I expect it will. However, I do read scholarly articles on screen. This is mostly to save paper, and I purposefully force myself to do school readings digitally.

I generally read comics in physical trades, but if I read issues I need to read them digitally. When Neil Gaiman started publishing his new Sandman story, Overture, I bought the physical issues as they came out in order to get the full Sandman experience. I never read them. I have the same problem that I did with the nonfiction ebook. I have the physical trade on hold at the library so I can read the series.

Mostly, I find instead of reading some genres digitally and some physically, I go through phases. Sometimes I only want to read ebooks. Sometimes I can’t focus on e-text and only read physical books. Currently I’m in a physical phase.

I don’t remember having weird reading habits like these before I got into ebooks. I suppose the amount of choice they afford let me explore all the methods of reading and subconsciously settle on my favourites. Maybe, in terms of nonfiction tomes, I’m still hung up on the perceived authoritativeness of physical text versus ebooks. As many of the ebooks I’ve read have had formatting problems and mistakes (and this includes ones I’ve bought as well as library books) this may not be a completely unfounded assumption.

In case anyone is interested, the book on rabies I will eventually read is called Rabid: a cultural history of the world’s most diabolical virus by Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy.

The Sandman: Overture is a prequel to Neil Gaiman’s excellent Sandman series.

![image[5]](http://metadefect.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/image5-300x225.png)

![image[2]](http://metadefect.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/image2-300x225.png)