‘Vincent van Gogh – The Letters’ is a “scholarly edition of all extant letters (902) sent by or to Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890)” (TEI, 2010). The TEI project page notes that, “Van Gogh’s correspondence is a unique resource for the insight it provides into both his artistic practice and his personal life. The full digital edition is available online; a reading edition is available as a six volume book edition. While intended for a scholarly audience, the edition is expected to serve the interest of a much wider public” (TEI, 2010).

The project, which is hosted by the Huygens Instituut, in collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam, provides for each letter, “a zoomable facsimile, a transcription of the original text (mostly Dutch or French), a new translation into English, and extensive annotation. More than 2000 illustrations are given of the works of art that Van Gogh mentions in his letters. Introductory essays discuss Van Gogh, his letters and his circle. Other material includes a timeline, maps, indices and a bibliography” (TEI, 2010).

Interestingly, the TEI project page also notes that, “the project started before the era of the web, and it was only later decided the web would be its main publication platform. The letters and annotations were created in a word-processing program and later converted semi-automatically into TEI (something that you probably want to avoid doing)” (TEI, 2010). It also describes how the project, “created one TEI (P5) document per letter, holding header information (we introduced some new header elements), facsimile information, transcription, translation and annotation. Other TEI documents hold secondary texts such as the essays and bibliography” (TEI, 2010).

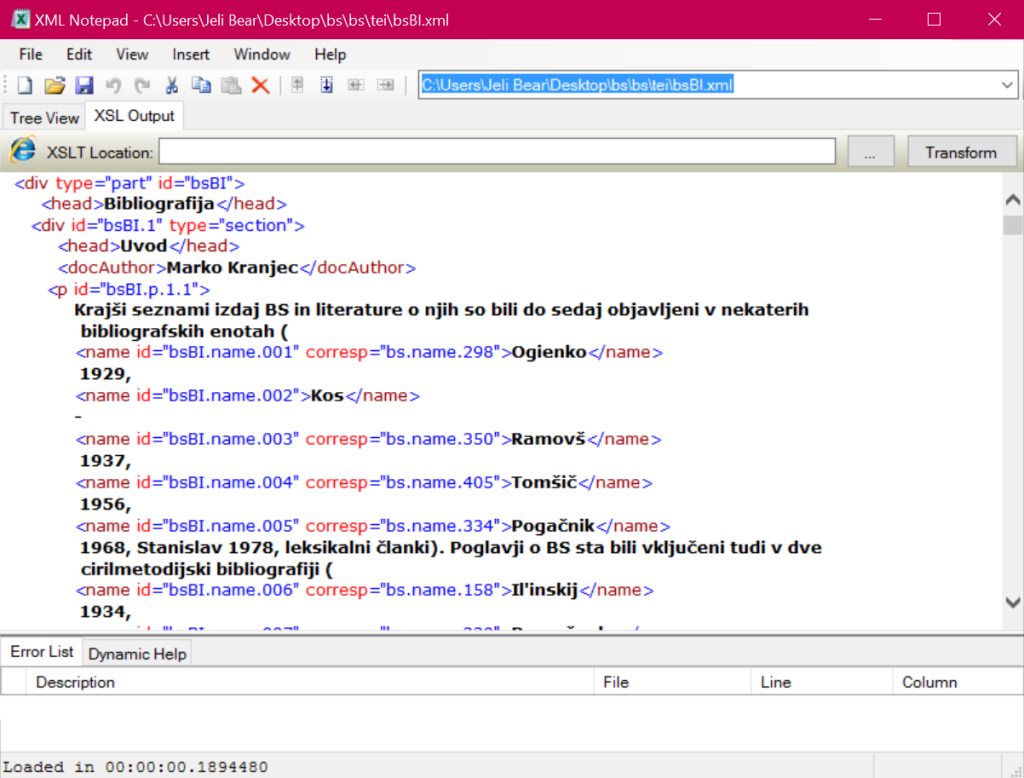

The website itself describes the use of XML generally – though it takes a bit of searching to find the link (under ‘About this edition’ – ‘The web edition’). It notes that: “This edition, like many modern digital editions, is based on XML (eXtensible Markup Language) documents. XML is a standard for the creation of documents in which the document text is interspersed with ‘tags’, brief labels that describe the nature and properties of the text fragments that they surround. The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) has proposed guidelines for the names and types of the tags to be employed in humanities texts. Out of the 400+ existing tags, a so-called ‘schema’ can be created that contains exactly those tags that are applicable to a certain type of document (such as a letter that is prepared for a scholarly edition). New tags can be defined when the existing tagset is insufficient. The schema describes the required and permitted tags in a class of XML documents. It can be used to check the correctness of these documents. A dedicated schema was created for the Van Gogh edition. A number of non-standard tags were used, some of which were ‘borrowed’ from the DALF (Digital Archive of Letters in Flanders) project” (Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker (eds.), 2009).

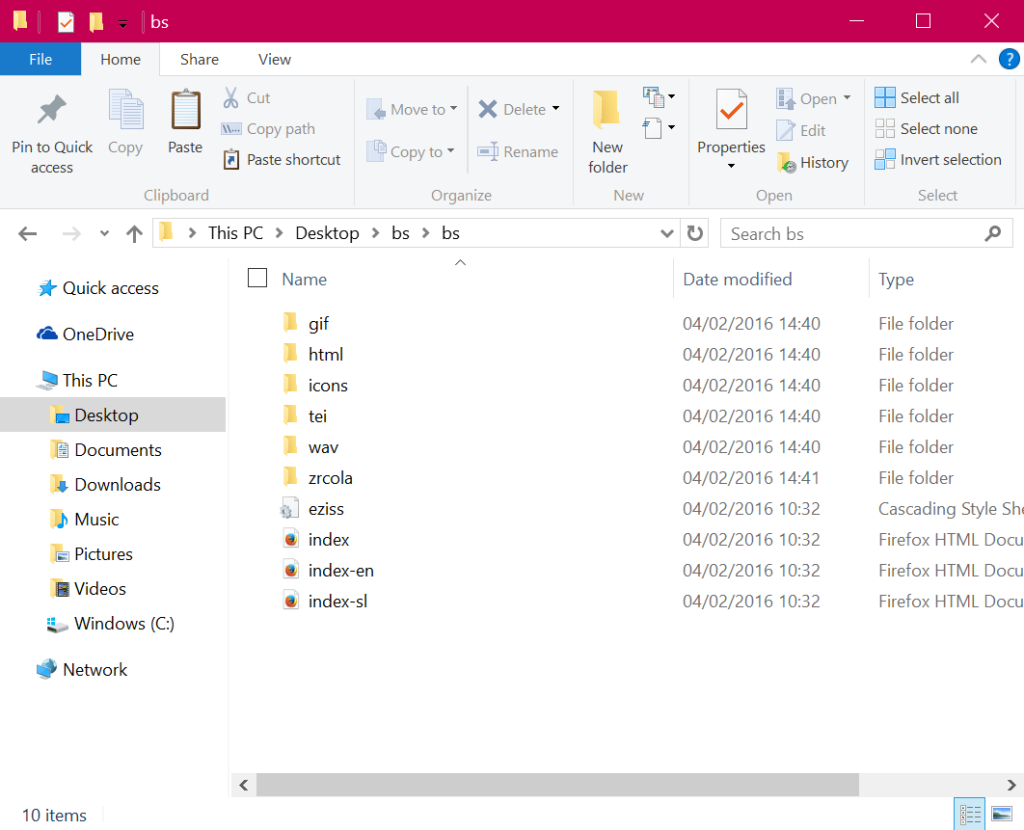

It then goes on to explain the specific use of XML for the project: “One XML document was created for each of Van Gogh’s letters and each related document. It holds letter-level metadata (title, number, date, correspondents, etc.), the full transcription, the translation, the notes, the textual notes, and the information that connects transcribed pages with images of those pages (facsimile elements). The XML files were created in an automatic conversion from word-processor documents. The conversion result was checked and extensively corrected. The XML files were manually indexed to facilitate searching and cross-referencing” (Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker (eds.), 2009).

I find it incredible to think that this XML was converted from word documents and not born digital!

The page even mentions that, “for those interested in technical matters, we provide somesample XML files. In the zip file we also include the so-called ‘ODD’ file which is used to customise the TEI schema and the schema files generated from the ODD-file. We use W3C schema rather than Relax NG because the contractors who performed the conversion to XML were more familiar with that format” (Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker (eds.), 2009).

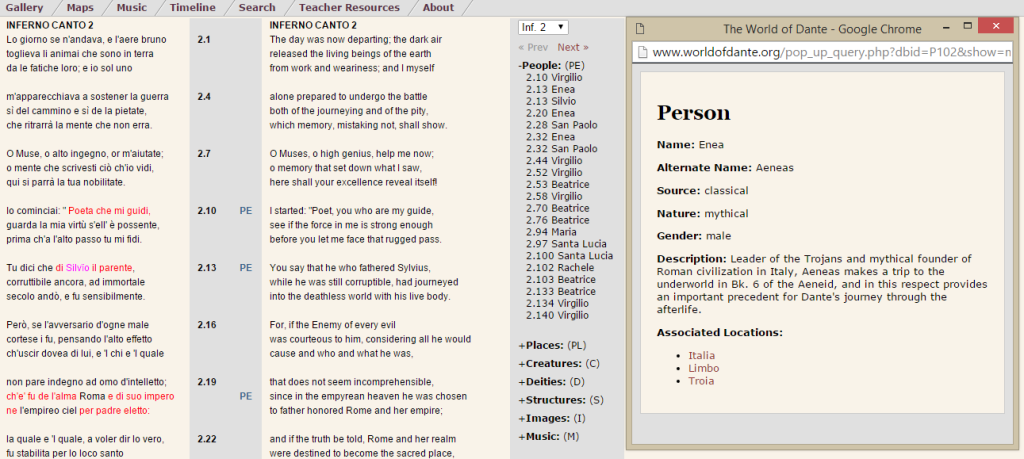

Here is an example of one of the XML files opened in word format:

The site also describes in detail the software tools that support the project. Overall, I am impressed with the degree of detail provided by the project, and their transparency with regards to the technical process.

Bibliography:

Text Encoding Initiative. (2010). Vincent van Gogh – The letters. http://www.tei-c.org/Activities/Projects/vi02.xml.

Jansen, Leo, Luitjen, Hans, and Bakker, Nienke (eds.) (2009). Vincent van Gogh – The Letters. Amsterdam & The Hague: Van Gogh Museum & Huygens ING. http://vangoghletters.org.