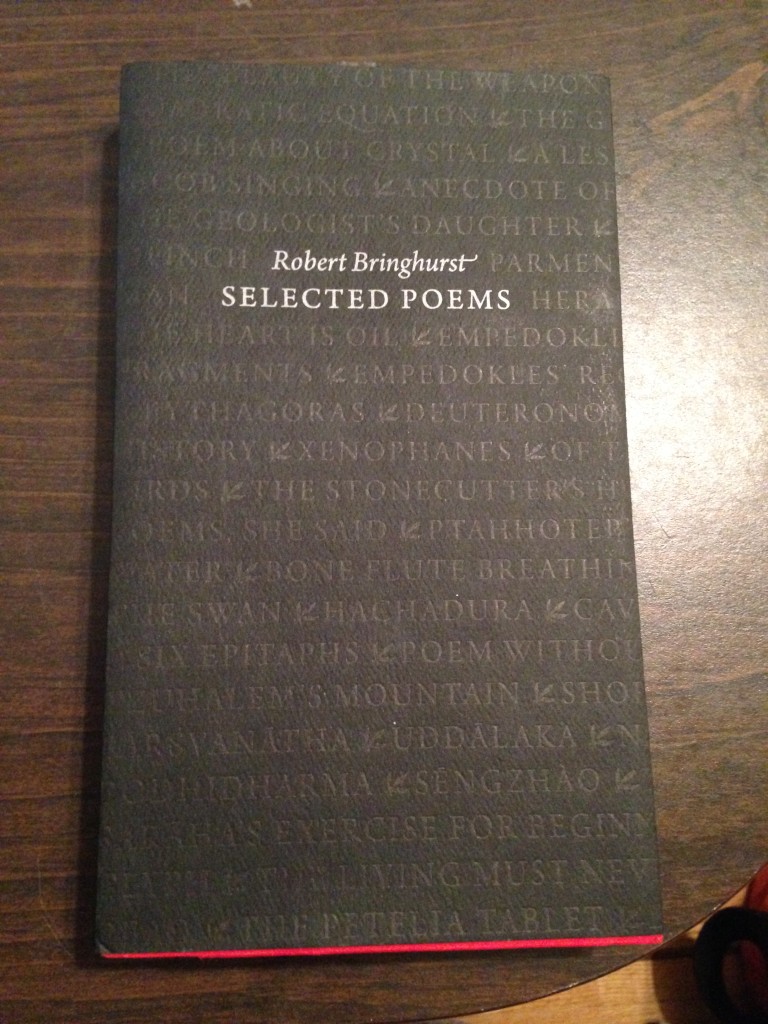

As Holly mentioned, she and I have chosen to work on a poem by the poet Robert Bringhurst for our encoding challenge. We have selected a poem from Bringhurst’s Selected Poems, published in 2009 by Gaspereau Press.

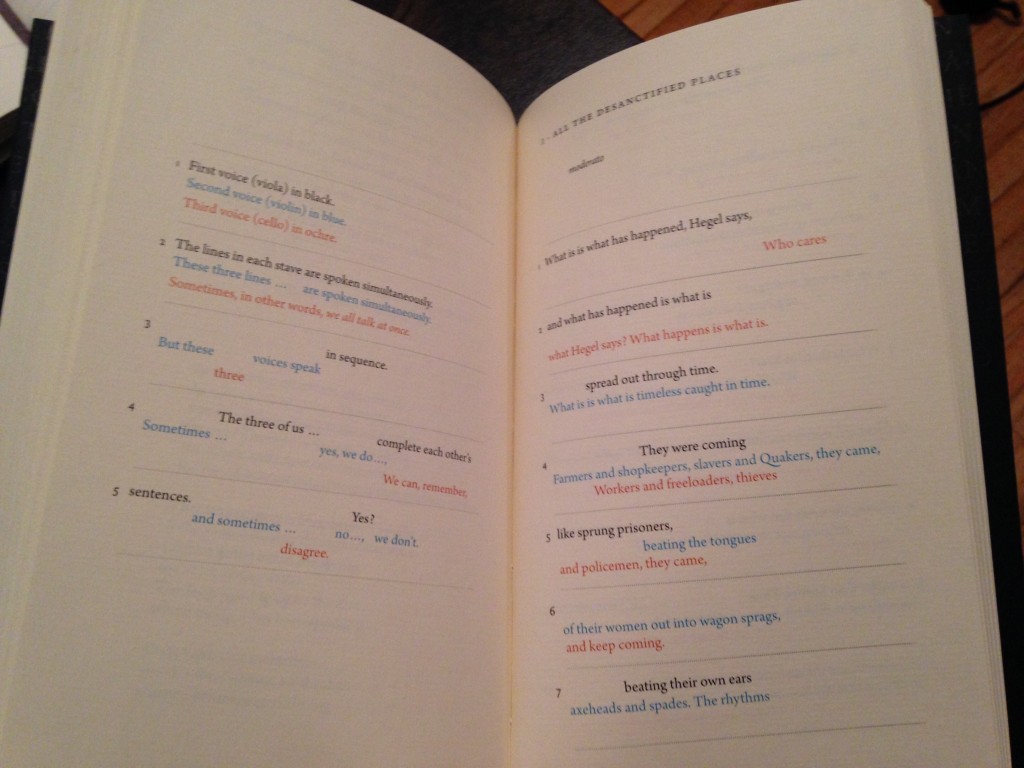

In an epigraph to the collection, Bringhurst notes that, “when conditions are right, it is good for poems to be spoken aloud. I mean that the poems themselves may benefit, not just the creatures who speak them and hear them. But in some of the poems in this book, two or three voices are speaking at once, contradicting or enlarging or refining one another as they go. Here, the overlapping voices are printed in different colors. Poems in which this occurs can be read in silence by one person alone or spoken aloud with one or two friends, if conditions are right. Which, in the presence of one or two friends, they just might be” (5). We felt that focusing on one of these poems with multiple voices was a great opportunity to explore what TEI allows us to capture of the experience of interacting with poetry. To begin, we looked at New World Suite No. 3: Four Movements for Three Voices:

If you’ll excuse the blurry photo…you can see perhaps that the three colours (black, blue, and red) represent the voice of the viola, the violin, and the cello, respectively. Bringhurst intends for the lines to be spoken simultaneously, at times, or in sequence. In some cases, the voices will finish each other’s sentences, or contradict one another. This sort of variety of reading experience immediately made me recall Prof. Galey’s example of his own work as part of his Visualizing Variation project, specifically his Animated Variants prototype (http://individual.utoronto.ca/alangaley/visualizingvariation/animated.html). Prof. Galey describes the project: “it was thought that digital editions could represent variants dynamically, presenting their ambiguity to readers not as a problem to solve, but as a field of interpretive possibility. Very few digital editions, however, have realized this possibility in their interfaces. One thing a digital visualization can do is make a virtue of ambiguity in ways that print cannot, combining the elements of time and motion to represent variants in ways that challenge the idea that texts are fixed and immutable.” This made me wonder if it would be possible to translate Bringhurst’s vision for a multi-vocal, performatory reading experience just as ‘dynamically’ as it is on the page, yet through XML. Exactly as Prof. Galey points out the potential for digital visualization, Bringhurst seems to be looking for the fluidity, the mutability, and the unfixed nature of this poetic interaction.

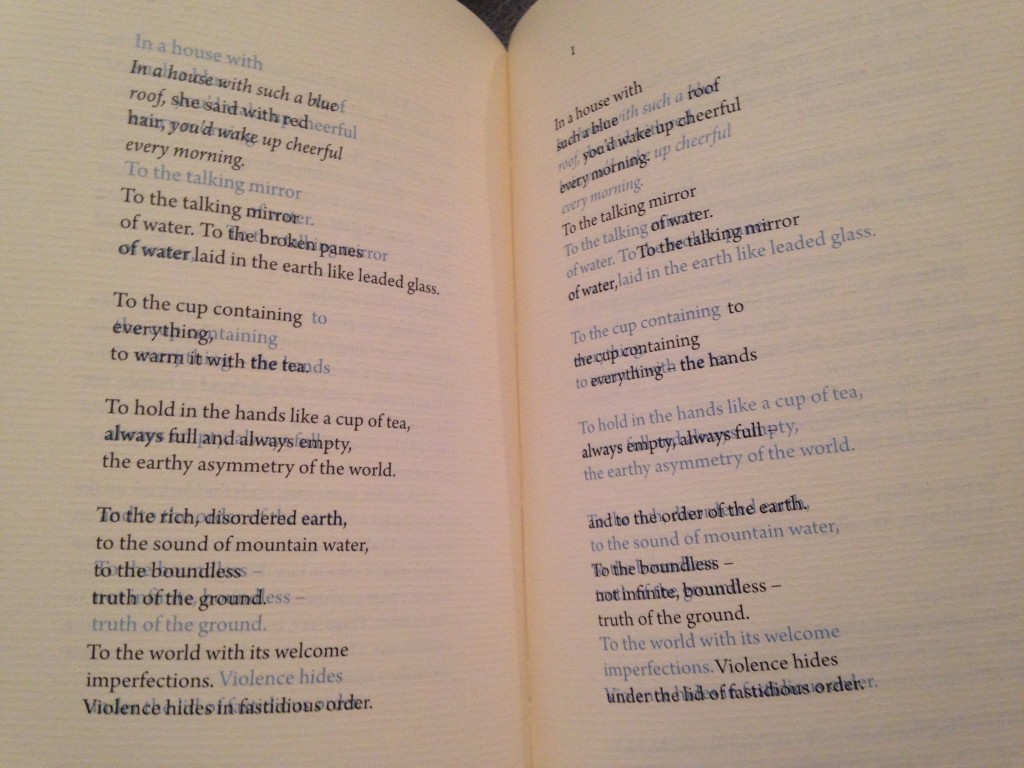

Upon considering the reflection further, Holly and I looked to another example of Bringhurst’s polyphonic poetry, The Blue Roofs of Japan: Duet for interpenetrating voices:

In an introduction to this poem, Bringhurst notes that, “The Blue Roofs of Japan is a poem for two voices – in principle little different from a sonata for cello and piano, except that here the instruments speak; they don’t quite sing. The full text of the poem is printed on both the righthand and lefthand pages of the book, but since the two voices frequently overlap, the two parts are not always legible on any one page. The lefthand pages give prominence to one voice, the righthand pages to the other. Facing pages should be read not in sequence but together. Reading the poem aloud requires two people…one reader, in any case, reads the black ink on the lefthand page while the other reads the black ink on the right. Under his or her own lines, each reader can see the other’s voice in blue. Enough blue ink is visible on every page to allow both readers to keep pace with one another. There isn’t, and in my view musn’t be, a metronome. The only thing the readers have to pace themselves against is each other” (175). It is exactly this sentiment that we hope to capture in our encoding. A sense of flow, overlap, and cohesion. As Galey points out, “animated variants also drive home the simple yet unsettling point that textual transmission is more often a matter of change than fixity: texts sometimes change even when readers aren’t looking.” Bringhurst opens up this possibility to his readers. While we’re unsure whether or not we’ll be able to execute our vision, we love the idea of applying something like CSS transitions (see: http://individual.utoronto.ca/alangaley/visualizingvariation/samples/animatedVariants/animatedVariants_v02_sonnet129.xml) to give the poem movement, colour, and ‘voice’, just as Bringhurst intended.

Bibliography:

Bringhurst, Robert. (2009). Selected poems. Canada: Gaspereau Press.

Galey, Alan. Visualizing variation. http://individual.utoronto.ca/alangaley/visualizingvariation/index.html#using.

Great post, Marlena!

Your initial discussion of the benefits of reading poems aloud made me think about how the written manifestation of something like a aural history is already at a representational remove. To encode a written text that was originally an aural “text” – which, in a way, has already been encoded – becomes an even more precarious endeavor. (I realize that is not the case with the poem you choose, but it got me thinking.)

Thanks David!

What you’re saying reminds me of one of D.F. McKenzie’s essays in ‘Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts’, called ‘The Sociology of a Text: Oral Culture, Literacy, and Print in Early New Zealand’. In it he describes the signing of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi – “On 6 February 1840 forty-six Maori chiefs from the northern regions of New Zealand ‘signed’ a document written in Maori called ‘Te Tiriti o Waitangi’, ‘The Treaty of Waitangi’. In doing so, according to the English versions of that document, they ceded to Her Majesty the Queen of England ‘absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of Sovereignty’ which they themselves individually exercised over their respective territories” (79). While this situation is certainly not unique in colonial histories – what McKenzie points out, in describing early missionary work with Maori alphabets and literacy is that, “what we have here is not only disillusionment about the actual extent to which literacy of the most elementary kind had been achieved, but a clear example of the way in which even the most sophisticated technology (print) will fail to serve an irrelevant ideology (an alien religion)” (108). He notes that, “historians have too readily and optimistically affirmed extensive and high levels of Maori literacy in the early years of settlement, and the role of printing in establishing it. Protestant missionary faith in the power of the written word, and modern assumptions about the impact of the press in propagating it, are not self-evidently valid, and they all too easily distort our understanding of the different and competitively powerful realities of societies whose cultures are still primarily oral” (109-110). This had profound affects on the Treaty signing – “consider the way in which the treaty was presented: it was read out in Maori by Henry Williams. That is, it was received as an oral statement, not as a document drawn up in consultation with the Maori, pondered privately over several days or weeks and offered finally as a public communique of agreements reached by the parties concerned….even the Maori language itself was used against the Maori…not only the concepts, but many of the words, for all their Maori form, were English” (113). McKenzie points out that “the English versions of the treaty have proved a potent political weapon in legitimating government of the Maori” while for the Maori “oral traditions live on in a distrust of the literal document, and in a refusal by many young Maori to accept political decisions based on it” (124, 125).

The essay is fairly complex and comprehensive, and I’m really not doing it justice here, but I think it has important things to say about how ‘encoding’ works in everyday life – in relations of meaning and power, especially. In another part, McKenzie writes that “for [the Maori] the really miraculous point about writing was its portability; by annihilating distance, a letter allowed the person who wrote it to be in two places at once, his body in one, his thoughts in another” (93).

If you’re interested, I would certainly check the essay out – it speaks seriously to how issues like literacy, print, and orality are both tools and myths, and how they mean entirely different things depending on who is wielding them.

McKenzie, D.F. (1999). Bibliography and the sociology of texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.