So, I plan on going back just three years, to 2013. My time machine isn’t very advanced, I suppose.

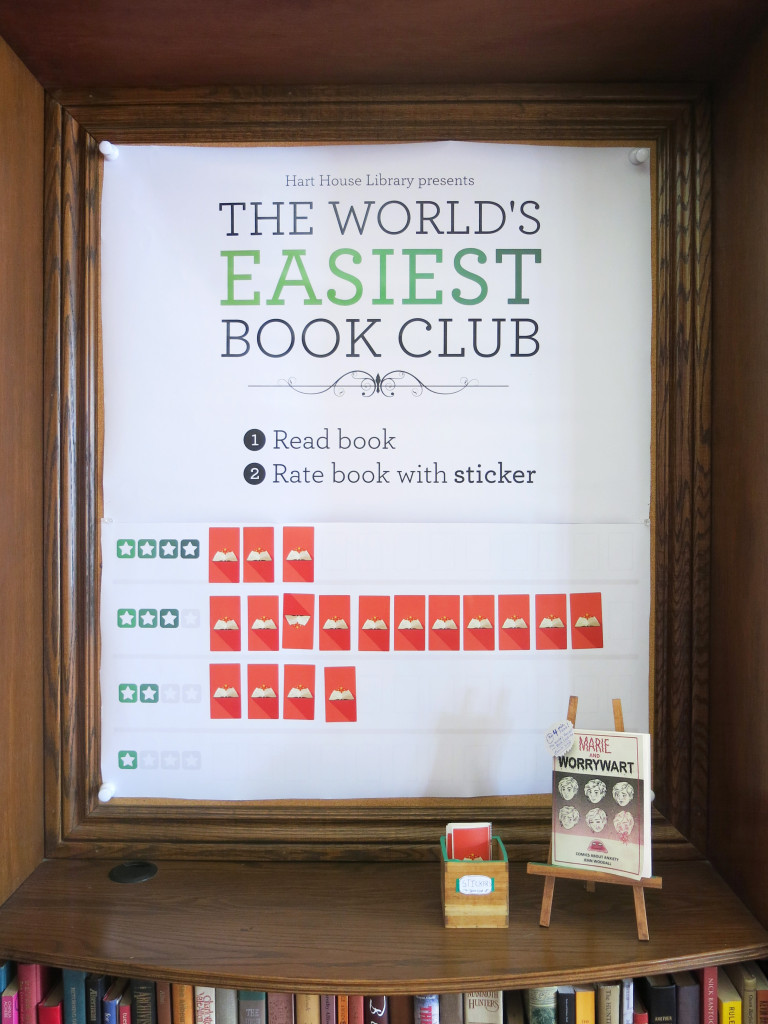

This is the year that the alleged first bookless public library opened: BiblioTech in San Antonio. This library loans out ereaders and, of course, ebooks while forgoing print books. My message would be about books and about libraries.

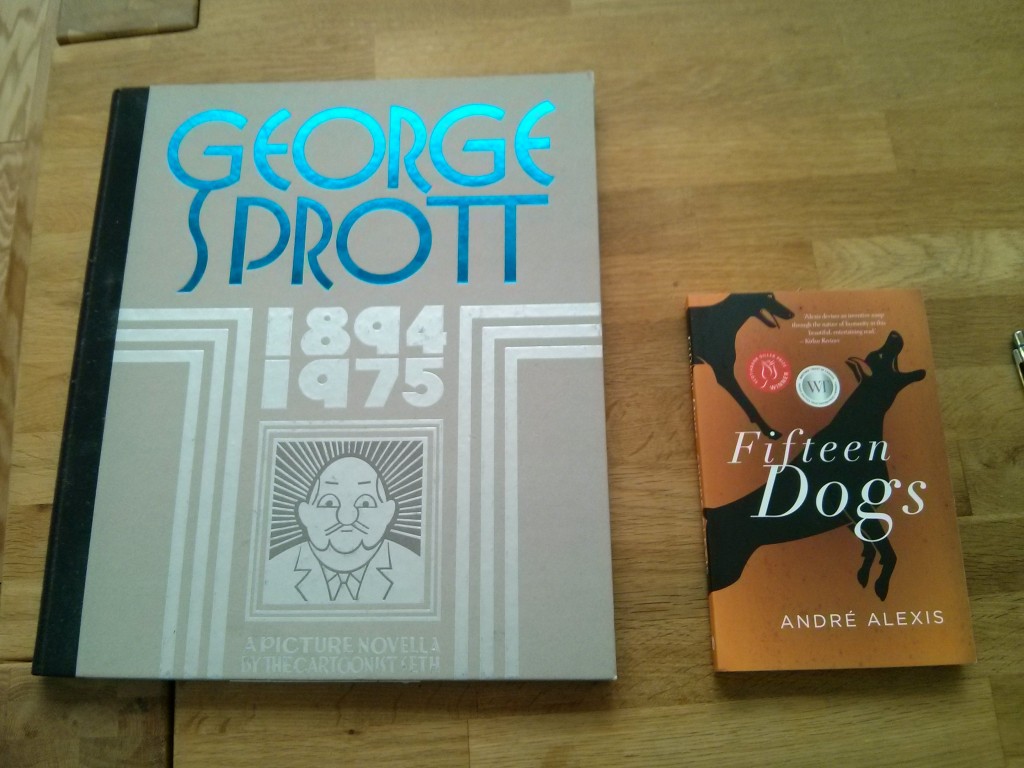

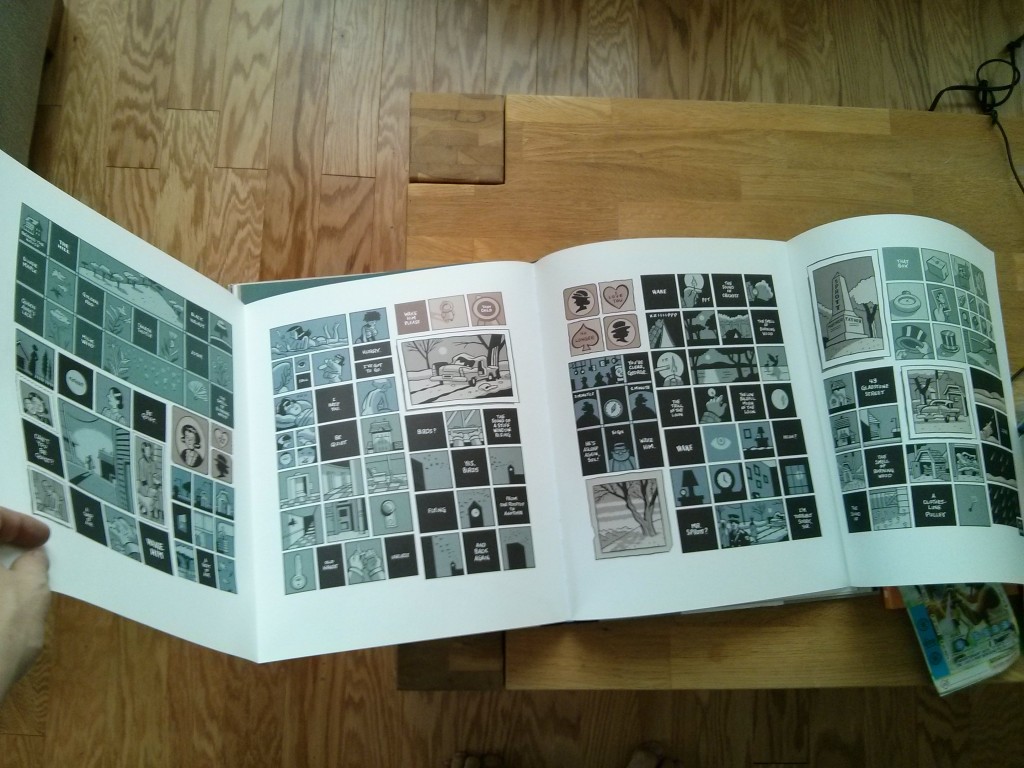

Regarding books, I would caution the library – and the world at large – that a binary decision between ebooks and print books is a false choice. In 2016, it is looking more and more likely that a hybrid model of books is here to stay for the short-to-medium term.

Regarding libraries, I would remind them that the immediate embrace of a bookless physical space may fail to capitalize on the library brand. Indeed, a 2010 OCLC survey showed that 75% of people associate libraries first and foremost with books (Gauder 38). This strong book brand should still be leveraged. Plus, in light of concerns about the longevity of digital media, “[p]aper is still the best medium of preservation, and libraries still need to fill their shelves with… paper” (Darnton 109-110). To that end, any local histories might be best stored as print books, not ebooks. An all digital collection is preparing for a future that may never becoming the present in our lifetimes.

Bibliography:

Darnton, Robert. The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future. New York: PublicAffairs , 2009. Print.

Gauder, Brad, ed. Perceptions of Libraries, 2010: Context and Community. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC, 2011. Print.