When I first read the blog question for this week, I could’t think of a book to discuss. After reading some of your earlier posts, a few childhood pop-up books and the like came to mind, but nothing in my memory really stuck out. However, when I went back to my notes on the Kirschenbaum and Werner reading, a light bulb turned on and I almost yelled “Eureka!”. Werner discusses annotations made by authors and readers, and the influence such annotations have on the content of the book. Werner also touches on Annotated Books Online, the digital archive of early modern annotated books.

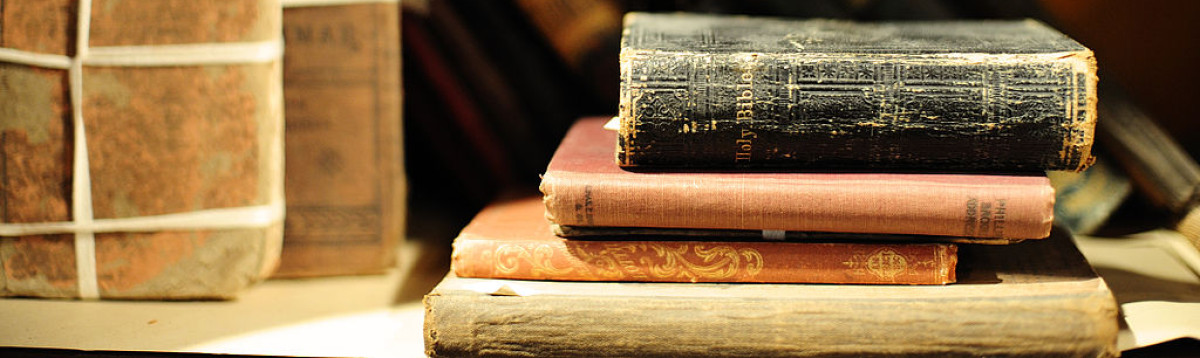

It was Werner’s discussion of annotation that brought to mind the Northrop Frye collection found at the E.J. Pratt Library at UofT. The collection includes material that was annotated by the literary scholar, among other items. It is interesting to note that is it not the books that give the collection its rarity but the annotations within these books that give them their true value. Frye’s personal thoughts are hand written between the margins of these books, giving them an additional dimension and influence, if not change, the meaning presented by the original author of the books.

This collection also came to mind because the annotations within the books pose a challenge for some forms of digital reading. I work for the Accessible Content E-Portal, as service offered by OCUL that provides digitized scans of materials for students with accessibility needs, offering these books in a variety of accessible formats. When selecting materials to scan for this service, I look for books with no marginalia. In cases where there has been marginalia made with a pencil, I am required to remove this marginalia so that it does not interfere with the OCR’s ability to translate the content of the PDF into a text format. However, removing these annotations is upsetting to some users who want to have the same experience as other readers, including the flow of thoughts of pervious readers. The additional dimension added with annotations is unobtainable for these users, and they cannot experience the affect they have on the original material.

If you would like more information about the Northrop Frye collection, please visit this website.

If you are interested in the ACE project, there is more information found here.

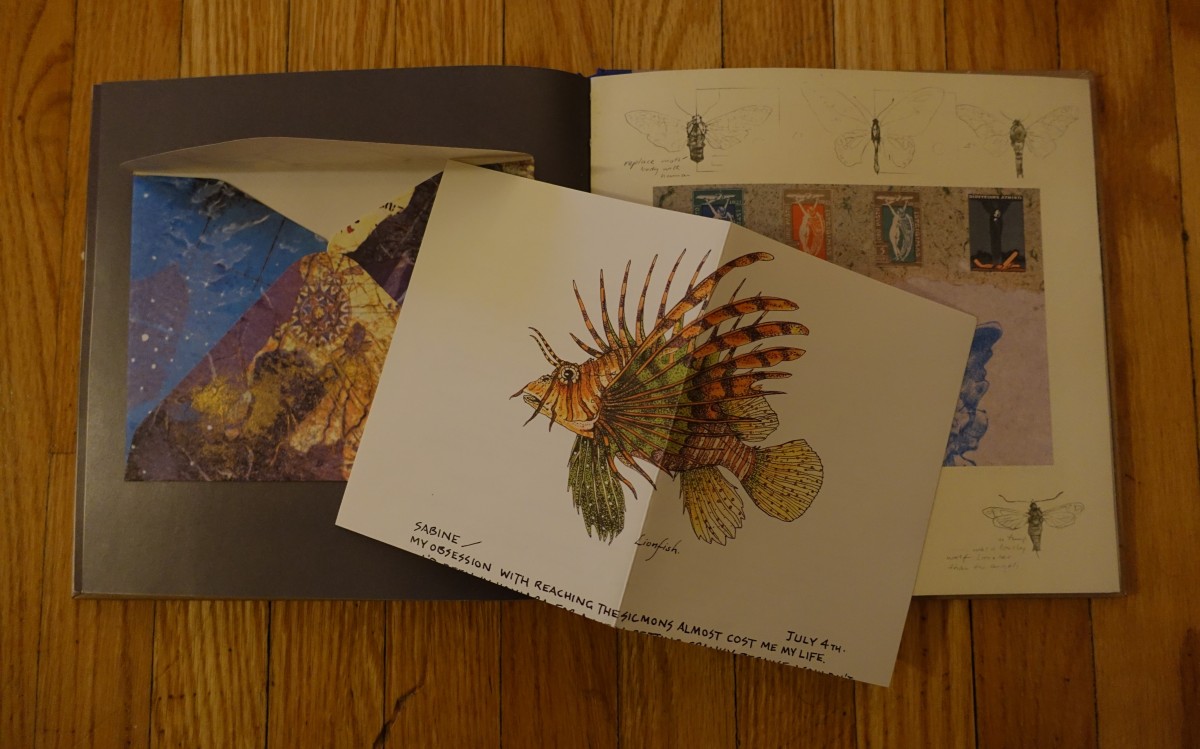

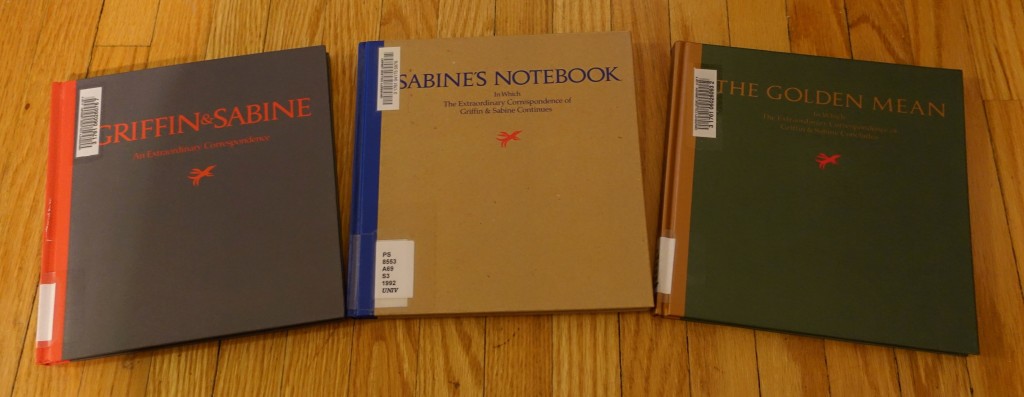

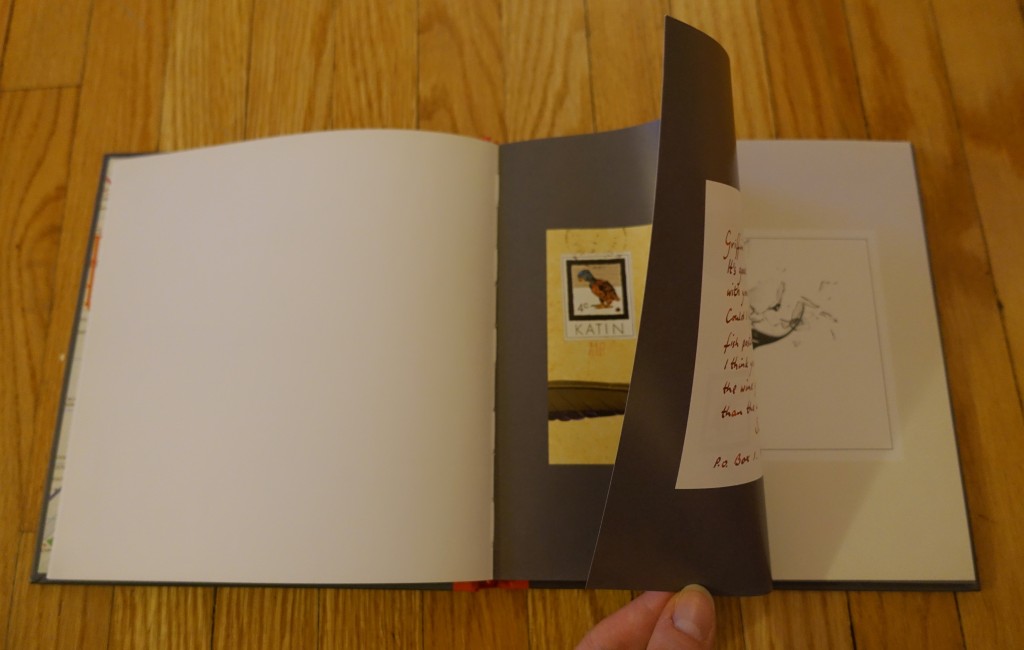

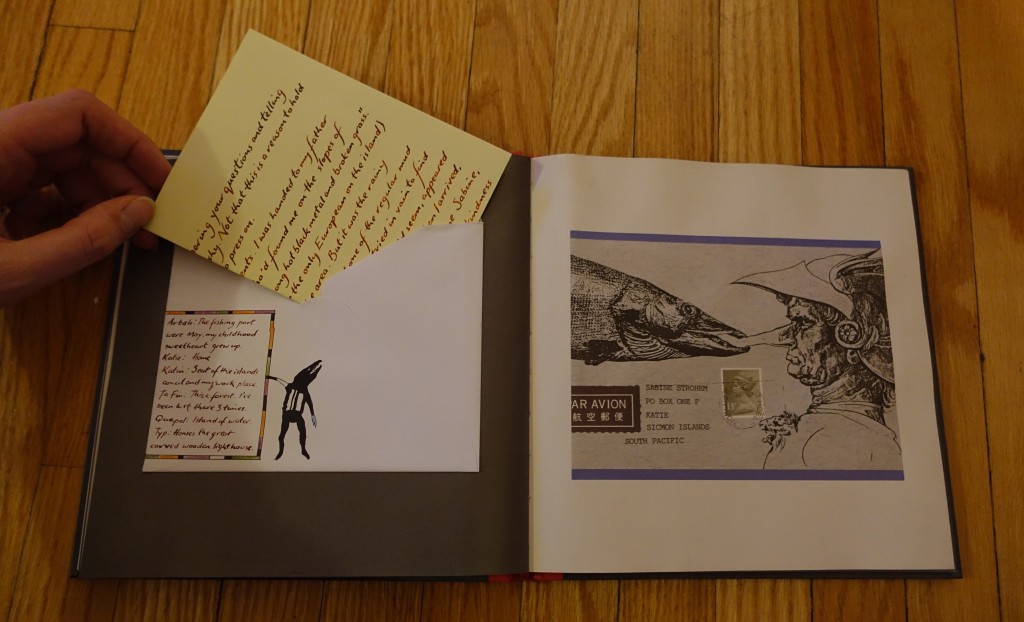

I recently came across Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence by Nick Bantock. The book is the first part of an epistolary

I recently came across Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence by Nick Bantock. The book is the first part of an epistolary

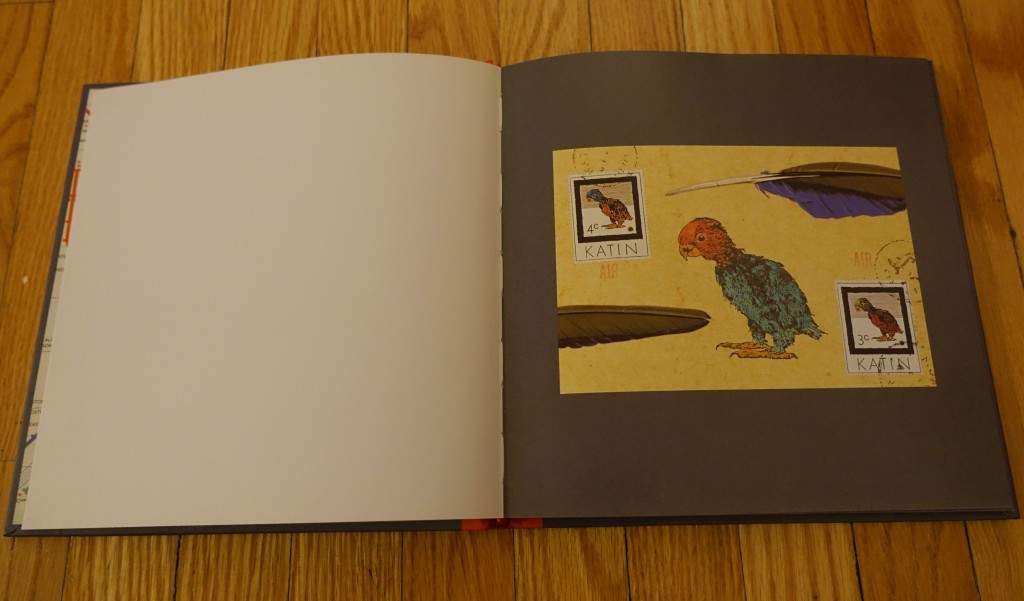

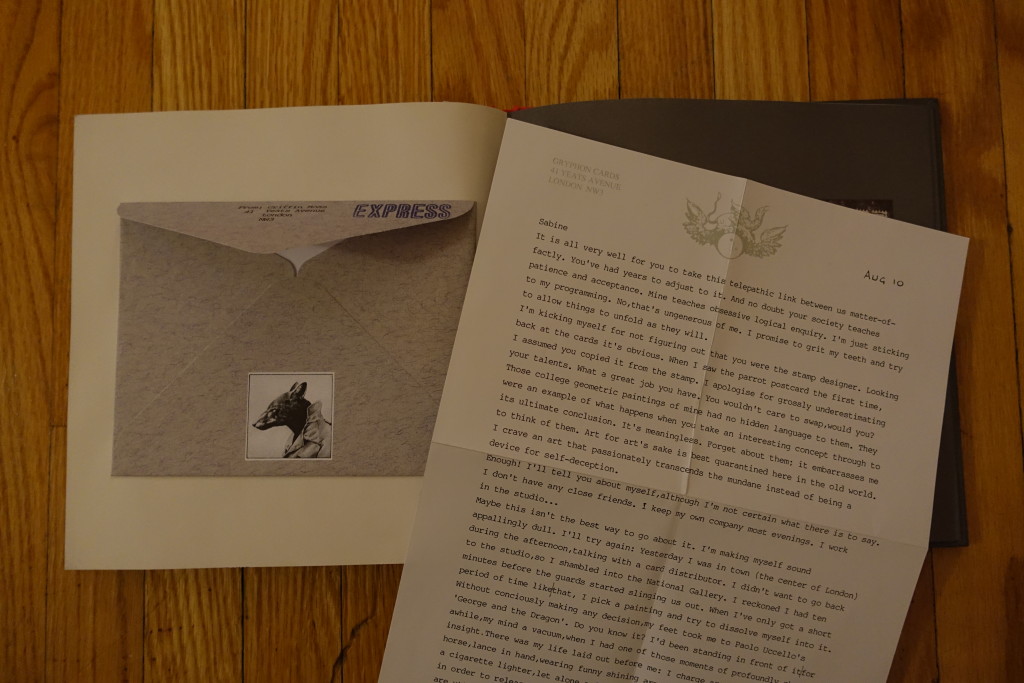

The benefit of the form is that Bantock can keep the correspondence free from obvious authorial intervention and really allow for the two characters to speak with their own voice. Unlike a typical epistolary novel, which is usually structured like a regular novel (maybe with various fonts to represent characters), this form allowed Bantock to show much of the characterization through the way the characters styled their letters.

The benefit of the form is that Bantock can keep the correspondence free from obvious authorial intervention and really allow for the two characters to speak with their own voice. Unlike a typical epistolary novel, which is usually structured like a regular novel (maybe with various fonts to represent characters), this form allowed Bantock to show much of the characterization through the way the characters styled their letters.